Ksenia Platonova

Notes on immigration and integration

Do you remember the concept of the “good enough mother”?

There is also such a thing as a “good enough place to live.”

For many, the homeland has failed to provide this — a space where one’s essential needs, both physical and psychological, could be met. This experience of disappointment, of not being fully held by the collective environment, mirrors the early frustration of a child who cannot find complete attunement in the mother.

Yet just as there is no perfect mother, there is no perfect place. The ideal environment does not exist. But a good enough place is something that can be found — a space that allows for growth, creativity, and belonging, even if it is not free from conflict or limitation.

Finding such a place is part of individuation: the journey toward inner wholeness that includes reconciling ourselves with imperfection — both within and around us.

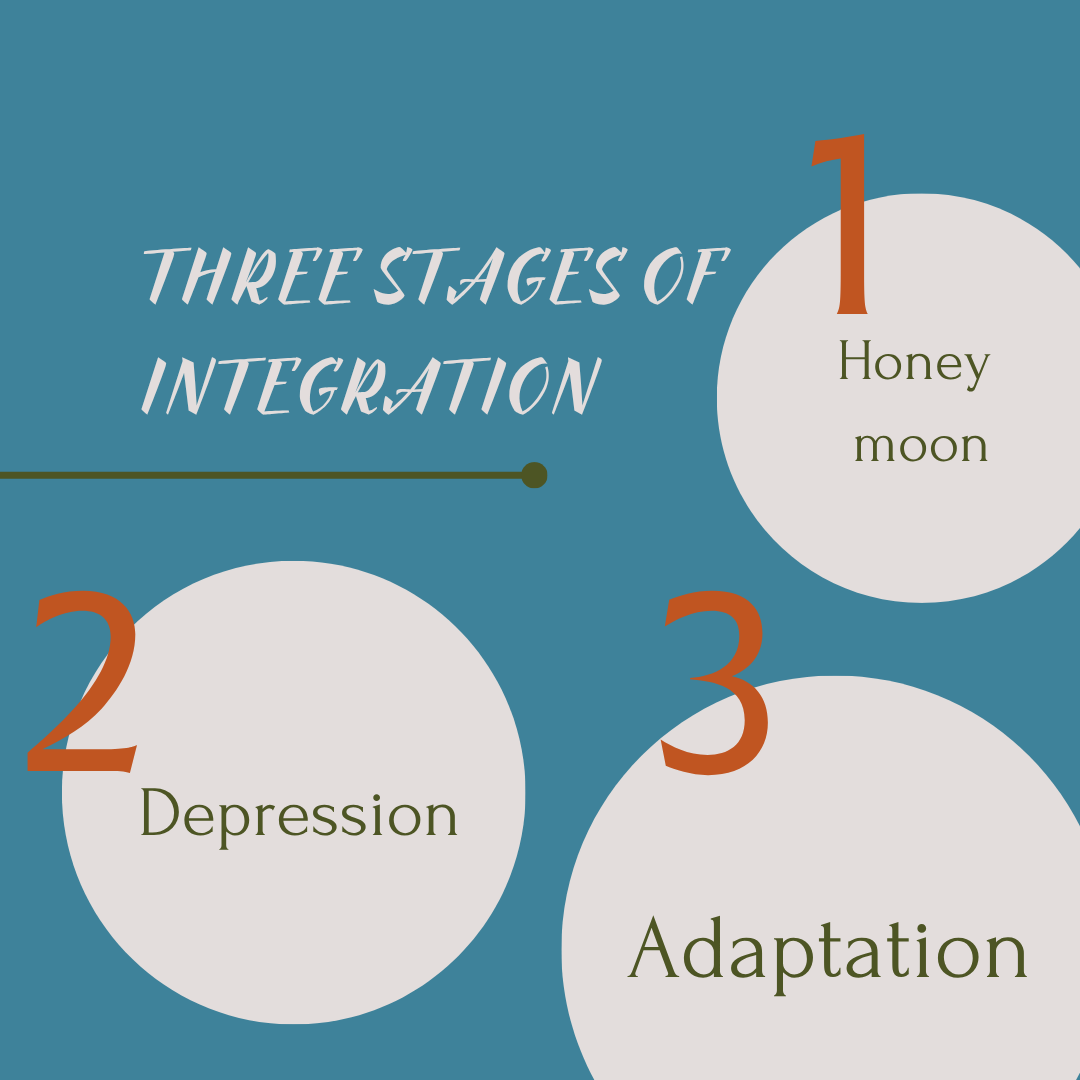

Let’s talk about the stages of integration.

The Honeymoon Phase

This stage shouldn’t be skipped. It’s essential to fall in love with the new place and gather enough energy to face the period of depression that often follows. During this time, everything feels exciting — Instagram overflows with photos of a new, wonderful life, surrounded by friendly, unfamiliar people. A light sense of euphoria creates the feeling that this new place is a perfect fit.

Unfortunately, for those who were forced to move, the honeymoon phase is often unavailable. But it’s never too late to create it for yourself intentionally.

Depression

Depression arrives when the sense of novelty fades. We begin to realise that there is no way back (if there truly isn’t one), and that the familiar, comfortable life must be rebuilt from scratch. The less contact we had with our emotions before the move, the harder this stage tends to be. Mourning your homeland, friends, favourite park, or café — all this is an important part of integration. We will talk a lot about this phase.

Adaptation

Adaptation is the process of accepting that things will never be the same as before — and allowing yourself to move forward. The heavy feelings have been lived through (though they may return from time to time). It’s time to act.

Have you experienced these stages? Which one are you in right now?

The process of seeking asylum — often described by the term “administrative abuse” — is, in itself, deeply traumatic. This has been confirmed by Irish researchers in their study “Mental health among persons awaiting an asylum outcome in Western countries” (International Journal of Mental Health, 38, no. 3).

The reasons are complex and multifaceted. During the asylum procedure, all the stress factors that a person has managed to balance and contain over many years become suddenly reactivated. Education, family relationships, financial insecurity, and unresolved emotional experiences — all these aspects, once held together by familiar structures, are thrown into uncertainty. The individual loses not only their sense of safety but also the continuity of their life story.

In Jungian terms, this experience represents a profound rupture in the psyche — a confrontation with chaos and the collapse of meaning. The external world mirrors an inner disorientation. And yet, this painful dissolution also carries the potential for transformation. When life’s foundations are shaken, the psyche begins to search for a new inner order, for symbols that can restore coherence and hope.

It is a difficult and disorienting path, but it is not without purpose — and you will find your way through it. Healing begins with acknowledging the depth of what has been lost, and trusting that even in the most uncertain times, the psyche has an innate capacity to move toward integration and wholeness.

Fear is an essential part of our survival mechanism. When the psyche detects danger, it signals the brain, which releases hormones and prepares the body to react and survive.

Changing one’s place of residence — stepping into an unfamiliar world — naturally awakens fear. To keep this fear from paralysing you, it’s important to understand what it’s trying to tell you. Sometimes, however, fear is not rational — it’s the fear of the unknown. And for a migrant, unfortunately, the world is full of the unknown.

This state of uncertainty can be extremely difficult for the psyche to bear. Yet there are ways to support yourself through it:

- Set time frames. Make short-term plans that focus on what you can control. For example: “I will stay in this apartment for one month; I have enough money for the next two weeks.” When the mind perceives even a small sense of order, the anxiety begins to loosen its grip.

- Value predictability. Create small rituals that bring a sense of safety — watch familiar movies, stay connected with loved ones online or offline, reach out for emotional support.

- Examine your worst-case scenarios. Imagine them clearly and ask yourself: “What would I do if this happened?” You’ll often discover that there’s always a possible path forward.

In Jungian terms, fear is not the enemy — it is the guardian at the threshold of transformation. When we listen to it with curiosity rather than resistance, fear becomes a guide, helping us take the next conscious step toward a new and more integrated life.

The psyche does not like the new. In analytical psychology, there is the concept of projection — a defence mechanism that operates both on the individual and collective levels.

For a person or a society, it is often difficult to face their own shortcomings, because acknowledging them means taking responsibility. It is much easier to repress these qualities into the unconscious and fight them at a distance. This is how projection works: what we cannot accept in ourselves, we attribute to others.

Thus, our own fears, aggression, or feelings of inadequacy are projected onto someone who appears different — the “other,” the foreigner, the neighbour who does not fit in. A fantasy arises: “If I get rid of the outsider, the problem will disappear.”

Migrants and displaced people often become victims of such projections. They carry the shadow of the collective — the parts of society it refuses to recognise. But, of course, the problem does not disappear. The shadow simply changes its form, continuing to seek expression until it is finally acknowledged and integrated.

As Jung wrote, “One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious.”

My son takes a couple of soft toys with him to kindergarten every day. I call them his “plush crew.” They link home and the new environment, creating a sense of continuity — a thread of being that stretches across spaces.

Adults, too, need transitional objects. Something familiar, something that carries a sense of home into the unknown, softening the anxiety of new beginnings. One of the best examples is a pet. A dog, for instance, creates a comforting rhythm of daily life — walks, feeding, care — a structure that persists even in times of uncertainty. Conversations with new people often start on a dog walk, gently weaving connection into the unfamiliar landscape.

Children can also become transitional figures for parents. They teach us spontaneity — the ability to inhabit new experiences without excessive fear or judgment. A friend once told me that, after moving to a new city, her little boy came home from the playground and said, “I met my best friend today.” “What’s his name?” she asked. He paused and replied, “I forgot to ask.”

If you don’t have a child or a pet, you can still find a symbolic transitional object — a familiar hobby, a volunteer project, a café or a place that reminds you of home. Something that carries emotional meaning, a bridge between the world you left and the one you are entering.

In Jungian terms, these objects help the psyche maintain continuity of identity while navigating transformation. They hold the tension between old and new, familiar and unknown — and, through them, we find a way to belong again.

Longing for a Lost Paradise

Sadness often accompanies the experience of migration — the ache of separation between what once was and what is yet to come. It is a quiet grief, born from the rupture between the familiar and the unknown. In moments when the challenges of assimilation feel overwhelming, the psyche instinctively seeks refuge — a safe inner space where everything is simple, familiar, and warm.

That is when we begin to idealise our homeland. Memories turn into myths; nostalgia paints them in golden hues. Against this dream of perfection, the new reality may seem dull, cold, or alien. Yet this longing — this “distance from paradise” — is part of the human condition.

In truth, there is no paradise on earth. What we miss is not a perfect place, but the feeling of belonging, safety, and meaning that once surrounded us. These emotions are not tied to geography — they live within us. The work of integration is to rediscover them in new soil, to plant new roots that echo the old ones.

Ask yourself: What exactly do I miss most? Is it the language, the smell of the seasons, the sense of being understood without words? And could there be something in this new place — a sound, a taste, a friendship — that might awaken the same feeling?

In Jungian terms, this longing is a call from the Self — an invitation to bridge the inner and outer worlds, to transform nostalgia into renewal. Through this process, we learn that paradise is not a lost place, but a state of inner wholeness that travels with us.

The Challenge of Learning a New Language in Migration

One of the most difficult aspects of the migration experience is often learning a new language. Yes, some people have a natural gift for languages, but for many of us, it can feel like an insurmountable barrier to integration. How can we make this process more manageable and even meaningful?

- Returning to the Classroom as an Adult – Sitting down to study in adulthood can stir up old memories. The psyche carries experiences of school and university: strict teachers, the shame of unfinished homework, and the pressure to be perfect. You might tell yourself, “I loved learning as a child,” but forget the hidden drive for perfection, the constant self-judgment, and the anxiety of not being the best. Even if those pressures are from the past, learning a new language can unconsciously trigger the same patterns: the inner critic awakens, and resentment toward the language grows.

- Atmosphere Matters – Enjoyment and curiosity are essential. How does it feel to listen to the new language or try speaking it for the first time? That moment when a random sentence in a shop suddenly makes sense — the pride and joy of the first independent conversation — is invaluable. Positive feelings become the strongest motivators.

- Support Your Psyche – Language learning is exhausting because the stakes are high: exams, social interactions, and the desire to communicate fluently. To sustain motivation, surround yourself with encouragement: a friendly and supportive teacher, a patient language partner, fun podcasts or TV shows, or a small conversation club with people who cheer your progress. This approach, rooted in pleasure and positive reinforcement, can be far more effective than endless hours of struggling through a dull classroom or trying to focus under pressure.

Reflect on your own experience: What helps you learn a new language? What gets in your way? In Jungian terms, the process of mastering a language is not just intellectual; it is deeply psychological. Each word, each conversation, helps integrate your inner world with the new outer world, bridging the self with the culture you are entering.